Eli Waldron (1916-1980) was a writer by profession and a draftsman by passion, though he excelled at both. Born and raised in Oconto Falls, WI, he first gained attention in the 1940s for short stories published in literary journals and magazines such as Story, The Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, Collier’s, and The Saturday Evening Post. Employing satire, humor, and surprise endings, Waldron’s short fiction often featured highly idiosyncratic characters who struggle against the limits of mainstream society to find acceptance and self-respect. For example, in “Come, Hercule” (The Kenyon Review, Summer 1944), a village outcast attains redemption through his association with a haughty and mysterious stray dog. Inventive and masterfully crafted, Waldron’s fable-like tales continue to captivate readers today just as they did when first published.

Waldron moved to Greenwich Village in 1947 and became part of a literary circle that included Richard Gehman, Hollis Alpert, Josephine Herbst, S. J. Perleman, and J. D. Salinger. In 1945, he was awarded the “Participation Award,” a literary prize by the publishing firm Simon and Schuster that allowed him to complete a novel. His resulting novella, The Low Dark Road, concerning two soldiers and a nurse in an Army psychiatric ward, received strong responses of both praise and criticism by Simon and Schuster’s editors, yet the book was ultimately not published. He went on to develop a career as a journalist, writing numerous and eclectic non-fiction articles that were published in Holiday, Gourmet, Rolling Stone, Publisher’s Weekly, and in The New Yorker. Pieces such as “The Lonely Lady of Union Square” (1955), drew praise from his editors, admiration from readers, and queries from major publishers.

Waldron was also a prolific and evocative poet who produced thousands of pages of verse. His poetry comprises lengthy works, such as “The Shooting of Andy Warhol” (1968) to very short poems, such as “The Archcrow” (ca. 1967). Throughout the 1960s and 70s, some of his poems and experimental fiction works appeared in [then] underground, counter-cultural, or alternative publications such as Illustrated Paper, Rat Subterranean News, Underground, The Village Voice, and The Woodstock Times.

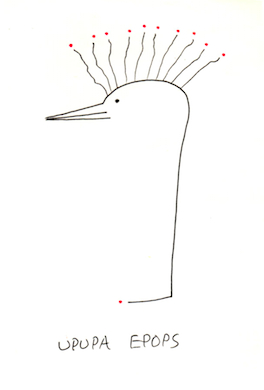

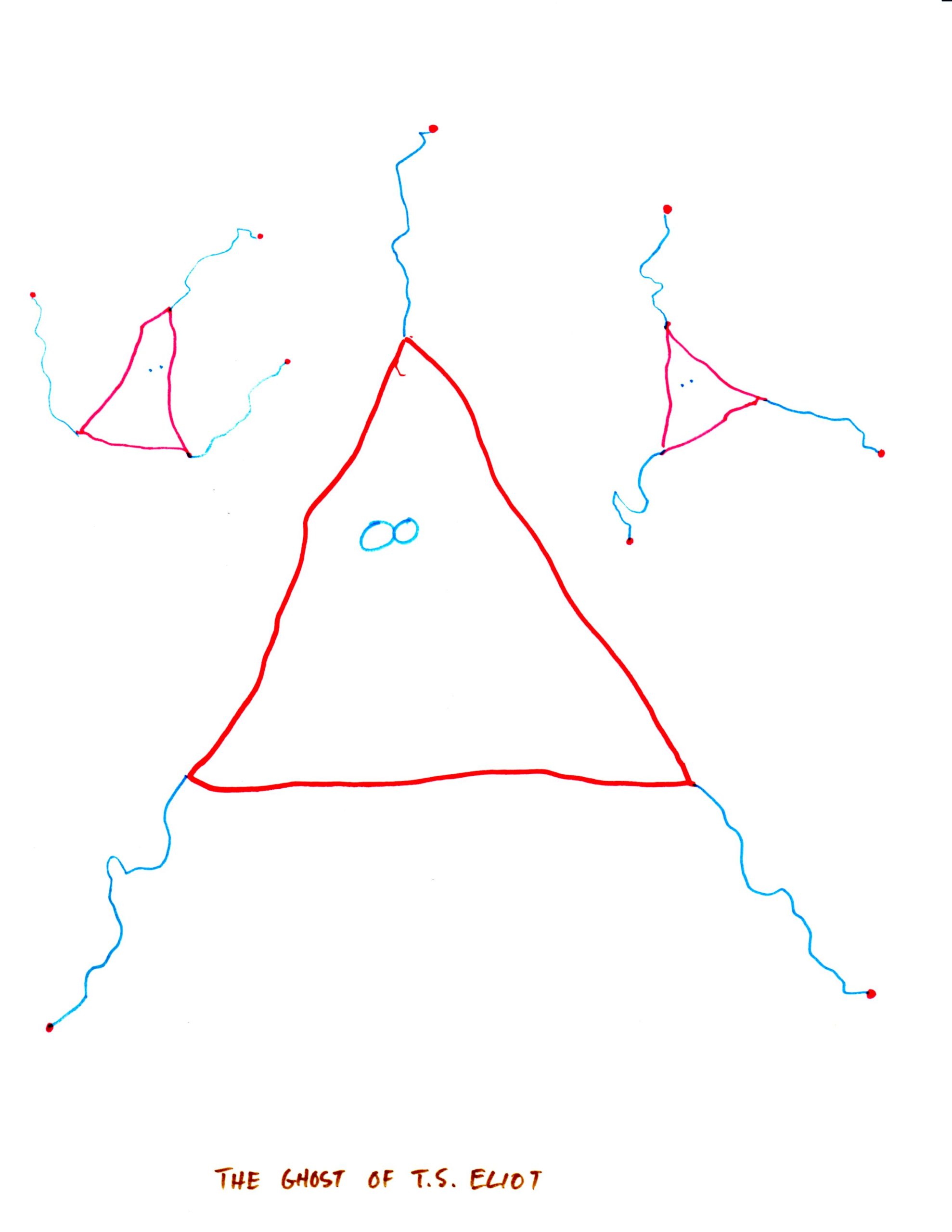

Waldron’s imaginative and often whimsical drawings, dating from the mid-1950s to 1980, are less well known than his literary work. Nonetheless, they form an important part of his oeuvre. In them, words and images coalesce to create a literary form of art. Many are captioned and deal with the themes of love, sex, nature, the individual, politics, power, spirituality, and the cosmos with concision, wit, and humor. Motifs include trees, birds, eyes, faces, and signs. A recurrent feature in the drawings is the profile of a long-nosed man, who could be said to represent the artist, observing. His drawings include single sheets, themed groups of related drawings, illustrated books, which combine drawings with prose or poetry, and word art, such as “IPGLOK,” (ca. 1973), in which words themselves, in unusual spellings and arrangements, are the subject of the work.

In a Waldron résumé prepared during the 1970s, he states: “Presently working on short stories in effort to complete a collection.” Despite a successful writing career that spanned four decades, he never saw a book of his collected works published in his lifetime, nor has one appeared since. Living in Woodstock, N.Y. since 1974 with his companion and then wife, Waldron died in a car crash in Culpepper, Virginia in 1980.

A remarkably talented writer, poet and illustrator, the literary and visual art of Eli Waldron continues to gain recognition and appreciation. Most recently, in 2013, The Kenyon Review published his story “Do Birds Like Television?” along with six of his drawings featuring birds, while the Kenyon College Library in Gambier, OH, featured an exhibition of his drawings and other materials from his archive.